The seven quotations below provide a window on to the arguments rehearsed in Modernism and Religion: Between Mysticism and Orthodoxy.

Evelyn Underhill

“[Mysticism] requires to be embodied in some degree in history, dogma and institutions if it is to reach the sense-conditioned human mind. [… T]he antithesis between the religions of ‘authority’ and of ‘spirit,’ the ‘Church’ and the ‘mystic,’ is false. Each requires the other.”

“[Mysticism] requires to be embodied in some degree in history, dogma and institutions if it is to reach the sense-conditioned human mind. [… T]he antithesis between the religions of ‘authority’ and of ‘spirit,’ the ‘Church’ and the ‘mystic,’ is false. Each requires the other.”

This quotation taken from the preface (1930) to the twelfth edition of Mysticism: A Study of the Nature and Development of Man's Spiritual Consciousness (first published in 1911) reveals the tensions at work in accounts of mysticism in the age of modernism. The study to which the preface is attached reconstructs a mystic’s progress through the stages of purgation, illumination and final union with God, using the psychological terminology Underhill discovered in William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience. Underhill’s Mysticism attends to the ‘rearrangement of the psychic self’ through the mystical journey and examines how the emergence of the ‘spark of the soul’, a term taken from the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart and which Underhill locates in the subconscious mind, reorientated a mystic’s life. The original study itself side-lines the emphasis the later preface places on ‘history, dogma and institutions’ and, through its emphasis on direct transformation of the individual psyche and deployment of a scientific register, Underhill’s Mysticism itself contributes to the ‘antithesis between the religions of “authority” and of “spirit,” the “Church” and the “mystic”’ that the preface opposes.

Underhill’s later understanding of the reciprocity between the institutional and the mystical came to her through her spiritual director, Friedrich von Hügel. Von Hügel’s study The Mystical Element of Religion situated his titular element alongside two more: the institutional and the rational. A healthy personal religion, Hügel contended, required ‘the harmonious blending of the three elements’ (Cuthbert Butler, ‘Religions of Authority and the Religion of the Spirit’, in ‘Religions of Authority and the Religion of the Spirit’ with Other Essays [London: Sheed & Ward, 1930], pp. 16–46 [p. 44n]). Underhill’s preface thus represented more than a change of mind. It is indicative of a response from institutional religions (and thinkers allied to them) to the challenges posed and opportunities represented by fascination in the age of modernism with new forms of mysticism and spirituality, which often drew on non-Christian sources, whether they be scientific, occult or other world religions. Modernism and Religion examines this cultural tension and positions modernist poetry within it.

Image: Evelyn Underhill in the conductor’s room at Pleshey. Photograph by the author of a plate in Margaret Cropper, Life of Evelyn Underhill (New York: Harper, 1958), p. 89.

William Inge

“The strongest wish of a vast number of earnest men and women to-day is for a basis of religious belief which shall rest, not upon tradition or external authority or historical evidence, but upon the ascertainable facts of human experience. The craving for immediacy which we have seen to be characteristic of all mysticism, now takes the form of a desire to establish the validity of the God-consciousness as a normal part of the healthy inner life.”

“The strongest wish of a vast number of earnest men and women to-day is for a basis of religious belief which shall rest, not upon tradition or external authority or historical evidence, but upon the ascertainable facts of human experience. The craving for immediacy which we have seen to be characteristic of all mysticism, now takes the form of a desire to establish the validity of the God-consciousness as a normal part of the healthy inner life.”

William Inge, the future Gloomy Dean of St Paul’s, was an Anglican cleric and scholar of mysticism; his Bampton lectures at the University of Oxford published as Christian Mysticism (1899) were a major touchstone for the study of mysticism. Inge’s account of religious attention and practice, set out in his introduction to the later anthology Light, Life and Love: Selections from the German Mystics of the Middle Ages (1904), is indicative of what Underhill opposed in her preface. Inge emphases the desire for a religious ‘immediacy’ evident in contemporary society and which has replaced a respect for the mediation of religious truth and the institutions that effected that. This new forms of religious engagement is shaped by science. ‘God-consciousness’ and a ‘healthy’ inner life redescribe religious life once marked by prayer, upright living and love of God and the neighbour. The church is no longer, as described in The Thirty-Nine Articles, the ‘visible Church of Christ’, striving to preach the ‘pure Word of God’ and minister the sacraments ‘according to Christs Ordinance’, so much as a setting where congregants’ psyches can be nurtured and strengthened (The Book of Common Prayer: The Texts of 1549, 1559, and 1662, ed. by Brian Cummings [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011], p. 679).

Image: William Ralph Inge, between 1911 and 1934, when he was employed as Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral, Library of Congress. Image courtesy of a Creative Commons license.

Martin D’Arcy

“[Mysticism seems] to gather together under one heading the strongly-felt beliefs of the churchgoer, the emotions felt by sensitive souls in the presence of sublime natural beauty, vivid and passionate faith, and the mystic states of such diverse persons as St. Plotinus, Francis of Assisi, [Percy Bysshe] Shelley, [William] Blake and St. John of the Cross.”

“[Mysticism seems] to gather together under one heading the strongly-felt beliefs of the churchgoer, the emotions felt by sensitive souls in the presence of sublime natural beauty, vivid and passionate faith, and the mystic states of such diverse persons as St. Plotinus, Francis of Assisi, [Percy Bysshe] Shelley, [William] Blake and St. John of the Cross.”

In The Nature of Belief (1931), Martin C. D’Arcy, a philosopher, Jesuit priest, and Master of Campion Hall, Oxford, took a different tack to William Inge. For Inge, the newfound interest in mysticism was part of a shift in the religious landscape. Mysticism, now understood in psychological terms, represented a newly significant religious phenomenon that spoke to contemporary needs. For D’Arcy, proponents of this new mysticism were merely confused. The pervasiveness of mysticism in contemporary society was not due to the emergence of new spiritual phenomena, but rather a willingness to gather under a single term, namely mysticism, several of the aspects of religion that were not dogma, theology and ethics. Mysticism, spirituality, the sacred more broadly, removed from their context in religious lives and practice, became divorced from reason and the production of knowledge and as a result transformed into mysterious, unknowable otherness. This process of intellectual ‘cleavage’ is, according to Michel de Certeau, one of the central features of an emerging secular age (Michel de Certeau, The Mystic Fable: The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, ed. by Luce Giard, trans. by Michael B. Smith, 2 vols [Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995, 2015], 2, p. 10).

Image: Howard Coster, Martin Cyril D'Arcy, half-plate film negative, 1938, NPG x11222. Image © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used via a Creative Commons license.

David Jones

“These, if the cult

grows strong, need hope and hope is only given

by the men of rule for their purpose, and so

it will be with your sibyls, baals, the lord

of the gibbet who would free the world.

Let them plant his signum where they choose —

let the empire acclaim him Rex, let Caesar

be the vicar of a Syrian mathematici, let

Roman Jove go hang, call the Great Mother

by some other name — what’s the odds?

The men of rule know all about such

trifles and how to accommodate, if needs

must”

“These, if the cult

grows strong, need hope and hope is only given

by the men of rule for their purpose, and so

it will be with your sibyls, baals, the lord

of the gibbet who would free the world.

Let them plant his signum where they choose —

let the empire acclaim him Rex, let Caesar

be the vicar of a Syrian mathematici, let

Roman Jove go hang, call the Great Mother

by some other name — what’s the odds?

The men of rule know all about such

trifles and how to accommodate, if needs

must”

In his work as a poet, David Jones spent much of his time following the publication of In Parenthesis (1937) working on a poem that centred on the conversations between the Roman soldiers of occupation in the Middle East at the time of the crucifixion. This work appears in The Sleeping Lord and Other Fragments (1974), The Roman Quarry (1981), and The Grail Mass (2018). It was initiated by a vision Jones experienced during a visit to Jerusalem in the mid-1930s where his sighting of British mandate soldiers in Palestine summoned up Roman antecedents (See Thomas Goldpaugh and Jamie Callison, introduction to The Grail Mass and Other Works [London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018], pp. 1–24 [p. 3]).

In the passage above from The Grail Mass, roman syncretism is pictured, by the lowly Roman soldier speaking, as coercive. In allowing the growth of local cults with an eye to appropriating them once they reached a certain scale, Rome discovered a new vector of power that helped contain the potential for dissent. The shrug of ‘call the Great Mother | by some other name — what’s the odds?’ illustrates the disdain in which non-Roman traditions are unofficially held. In their nonchalance, the ‘men of rule’ are contemptuous of even their own culture. The imperial mindset leads Rome (and by implication the European empires of the twentieth century) to dismiss out of hand symbolic life of all stripes. Any cult that grows sizable enough is shunted into the state religion. Distinctive features of weaker traditions are disregarded to present the ‘sibyls, baals, the lord | of the gibbet who would free the world’ as a type of the appropriate Roman deity. Creative expression is transformed, co-opted and turned against its creators rather than recognised and celebrated. For Jones, the mystical element of religion is the elusive, creative dimension of religion that is all too easily disregarded in a contemporary society structured by empire and industry.

Image: Front cover of David Jones's The Grail Mass and Other Works, ed. by Thomas Goldpaugh and Jamie Callison (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018). Image courtesy of Bloomsbury Academic.

T. S. Eliot

“You say I am repeating

Something I have said before. I shall say it again.

Shall I say it again? In order to arrive there,

To arrive where you are, to get from where you are not,

You must go by a way wherein there is no ecstasy.

In order to arrive at what you do not know

You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance.

In order to possess what you do not possess

You must go by the way of dispossession.

In order to arrive at what you are not

You must go through the way in which you are not.

And what you do not know is the only thing you know

And what you own is what you do not own

And where you are is where you are not”

“You say I am repeating

Something I have said before. I shall say it again.

Shall I say it again? In order to arrive there,

To arrive where you are, to get from where you are not,

You must go by a way wherein there is no ecstasy.

In order to arrive at what you do not know

You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance.

In order to possess what you do not possess

You must go by the way of dispossession.

In order to arrive at what you are not

You must go through the way in which you are not.

And what you do not know is the only thing you know

And what you own is what you do not own

And where you are is where you are not”

While the notes of the mystic St John of the Cross ring out clearly in these lines, his voice is not the only one audible. There is contained within this passage both the mystic’s gnomic wisdom and the fussing of the narrator; the interaction between the two is central to what is going on here. The narrator’s voice is characterised by a parenthetical, self-correcting syntax: ‘You say I am repeating | Something I have said before. I shall say it again. | Shall I say it again?’ The lines are coloured by both heavy caesurae and a hesitant, self-questioning tone. The narrator’s voice contrasts with the mystic’s riddles, which are marked by coincidence of line and sense unit; across two-line units, the adverbial clauses (‘In order to possess what you do not possess’) complete the first line and the main clause the second (‘You must go by the way of dispossession’). The mystic’s voice betrays a studied calm that serves as a counterpoint to the narrator’s befuddlement.

A distance thus opens between St John of the Cross and the poem more broadly. Responding to this difference, Modernism and Religion presents Four Quartets as not a mystical poem in and of itself, but rather a poem that is desperately trying to deploy mystical texts, religious experiences of its own devising, and reflections upon them in contemporary contexts to serve a particular purpose: to speak to a largely secular audience facing the anguish of wartime defeat. Far from acting as a guide, St John of the Cross gestures in a direction otherwise closed off to the poem. His voice, notably distinct from the harried utterances of the speaker, is merely tried out for a moment. Eliot would try a different approach to the mystical in ‘Little Gidding’.

Image: Lady Ottoline Morrell, Thomas Stearns Eliot, 1934, photograph. Image courtesy of a Creative Commons license.

H.D.

“the sun and the seasons changed,

and as the flower-leaves that drift

from a tree were the numberless

tender kisses, the soft caresses,

given and received; none of these

came into the story”

“the sun and the seasons changed,

and as the flower-leaves that drift

from a tree were the numberless

tender kisses, the soft caresses,

given and received; none of these

came into the story”

In Helen in Egypt, one of the central dramatic moments is Helen’s rejection of the joyous romantic relationship she enjoyed with Paris before and during the Trojan War and the acceptance of a different kind of relationship with Achilles. The decision is captured in the passage above. The unwinding of a simile that compares the volume and delicacy of falling leaves to a lover’s caress contemplates the sensuality of a romantic partnership in terms Paris would have recognised. Such tenderness represents, for Helen, only the briefest of moments. The poem quickly jerks free from the reverie in the syntactic recapitulation of ‘none of these | came into the story’. All that one might dare to hope to gain from a romantic relationship is to be put out of mind. The conventions of romance (‘tender kisses, the soft caresses’) are briefly entertained before their dismissal in favour of an ascetic commitment to what Helen later calls the ‘epic, heroic’. Modernism and Religion uses the religious philosophy of personalism, practised by figures such as Emmanuel Mounier and Denis de Rougemont, to understand this decision. Personalism itself reflects another response to mysticism along the lines established by Evelyn Underhill’s 1930 preface and links Helen’s ascetic actions to a broader anti-war project pursued through the imagining of different forms of social organisation.

Image: Man Ray, H.D., 1917, photograph. Scan of a photographic plate from Amy Lowell, Tendencies in Modern American Poetry (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1917), p. 233. Image courtesy of a Creative Commons license.

‘The Vision’

“God is realized most directly in seclusion and quiet [….] Looking back upon the old days it seems, indeed, strange to many of us now that we should have come to rely so exclusively as we did upon organisations, clubs, missions, – upon everything in short that is not quiet – for the deepening and extending of our Christian faith and life.”

“God is realized most directly in seclusion and quiet [….] Looking back upon the old days it seems, indeed, strange to many of us now that we should have come to rely so exclusively as we did upon organisations, clubs, missions, – upon everything in short that is not quiet – for the deepening and extending of our Christian faith and life. ”

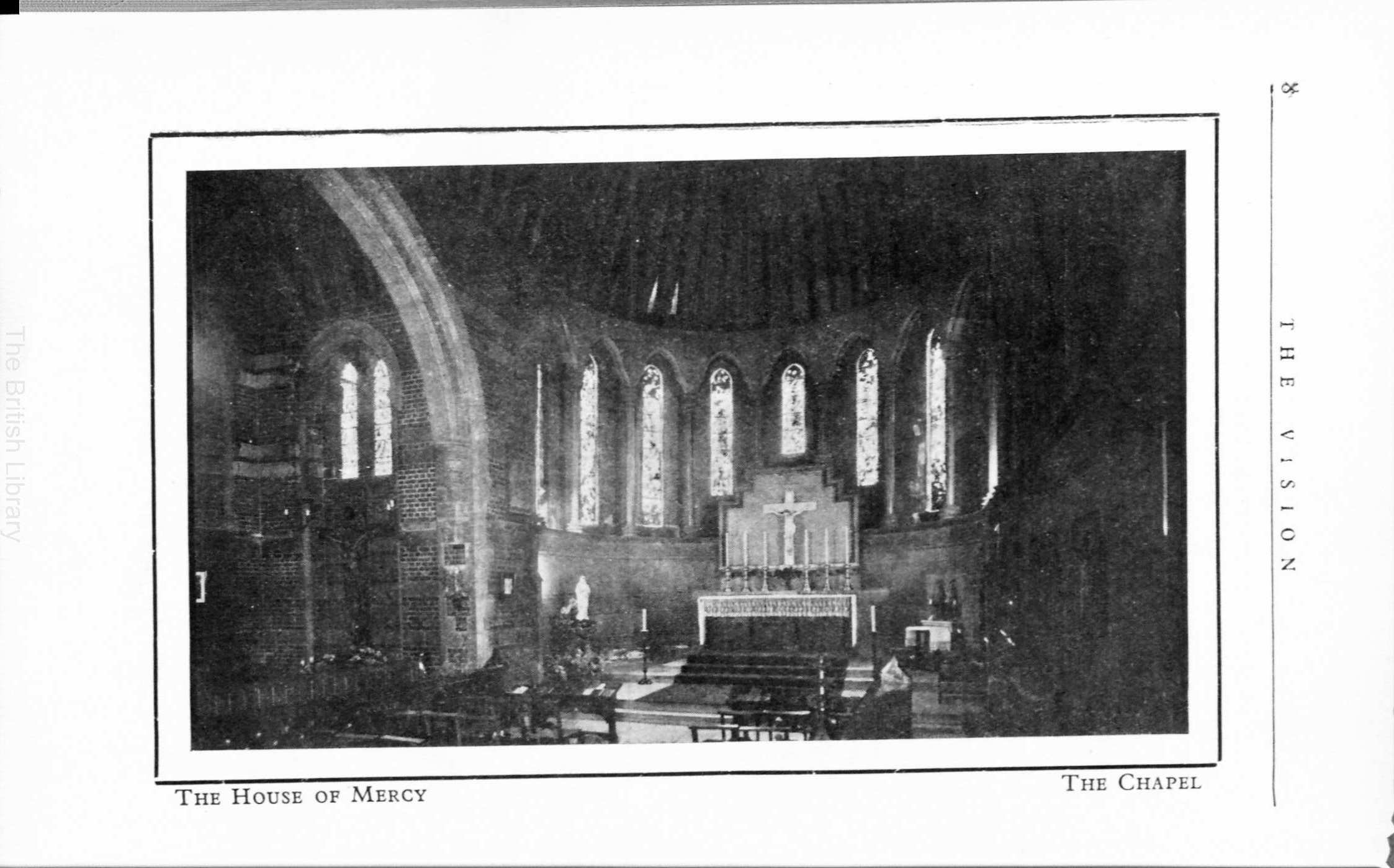

The Association for Promoting Retreats (APR) was formed in 1919 to develop retreat opportunities for laypeople. The organisation understood its work as responding to a decline of institutional religion and as representing a departure from the typical methods employed by the Church of England. In early numbers of the APR’s house journal The Vision, Canon Alan H. Simpson, the founding editor, opposed the APR to the established bureaucratic competence of the church or the ‘old ways’ of ‘organisations, clubs, missions’. Religious crisis was to be addressed not by imitating the administrative state’s bureaucratic procedures, but rather through the power of ‘quiet’ in and through which retreatants could be reformed and remade. In line with aspects of Underhill and personalism, here the mystical aspects of religion – reflection on or time alone with God – are placed at the centre of institutional religion rather than representing an alternative outside it. The shift in turn has repercussions for the way the church organises itself. Simpson sees the rise of retreat as signalling the end of the ‘old ways’. Orthodoxy, by this measure, has itself become mystical.

Image: The Chapel, The House of Mercy, Horbury, Yorkshire. reproduced from The Vision, 72 (October 1937), p. 8. Digital image courtesy of the author.